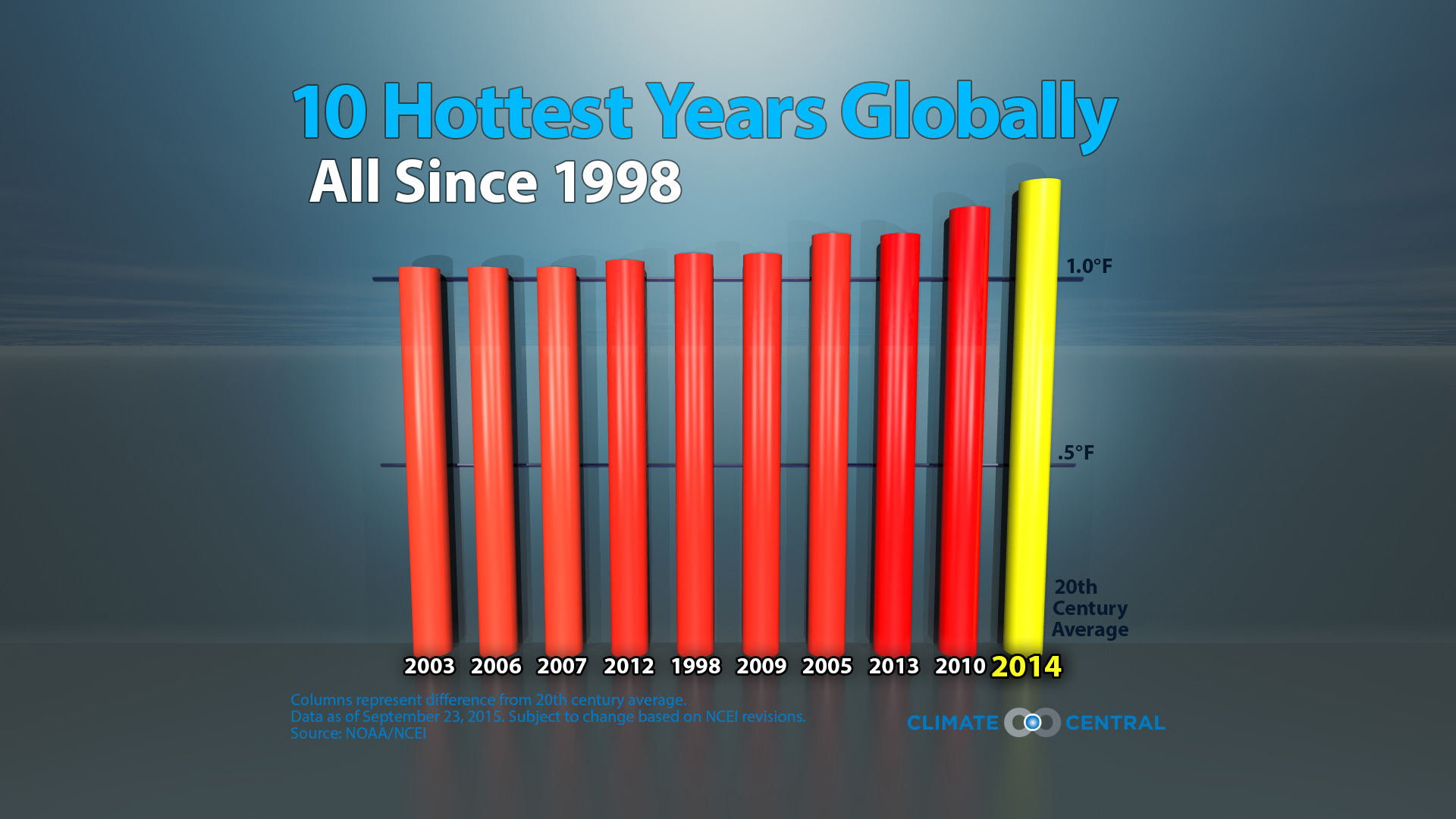

Personal Loans for 670 Credit Score or Lower Personal Loans for 580 Credit Score or Lower The Japanese Meteorological Agency and the World Meteorological Organization said the world has just gone through its hottest week on record.Best Debt Consolidation Loans for Bad Credit Eleven of the first dozen days in July were hotter than ever on record, according to an unofficial and preliminary analysis by University of Maine’s Climate Reanalyzer. July is usually the hottest month of the year, and the record for July and the hottest month of any year is 62.08 degrees (16.71 degrees Celsius) set in both July 2019 and July 2021. That’s because it’s likely only to get hotter. Children cool themselves with electric fans as they take a rest on a hot day near the Forbidden City in Beijing on June 25. Berkeley Earth’s Robert Rohde said his group figures there’s an 80% chance that 2023 will end up the hottest year on record.

NOAA says there’s a 20% chance that 2023 will be the hottest year on record, with next year more likely, but the chance of a record is growing and outside scientists such as Brown University’s Kim Cobb are predicting a “photo finish” with 20 for the hottest year on record. The first half of 2023 has been the third hottest January through June on record, behind 20, according to NOAA.

The Caribbean region smashed previous records as did the United Kingdom. But the globe’s sea surface - which is 70% of Earth’s area - has set monthly high temperature records in April, May and June and the North Atlantic has been off the charts warm since mid March, scientists say. “We are just getting a small taste for the types of impacts that we expect to worsen under climate change.”īoth land and ocean were the hottest a June has seen. “The recent record temperatures, as well as extreme fires, pollution and flooding we are seeing this year are what we expect to see in a warmer climate,” said Cornell University climate scientist Natalie Mahowald. The increase over the last June’s record is “a considerably big jump” because usually global monthly records are so broad based they often jump by hundredths not quarters of a degree, said NOAA climate scientist Ahira Sanchez-Lugo.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)